SOUTH AFRICA AS A CASE STUDY

The burden of mental health is very real in developing countries such as those in sub-saharan Africa. Recent studies have shown there to be only one psychiatrist for every 390,000 people in South Africa. Furthermore, two thirds of South Africa’s psychiatrists are employed in private practice.

Since November 1997, the European Commission has been sponsoring a project, designed to investigate such issues related to mental health in several sub-saharan Africa countries: South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The collaborative work of the six partner institutions involved in the project has yielded interesting ideas, which could be implemented in order to improve the general state of mental health in developing nations.

In aiming to improve mental health in any country, one needs to first evaluate the existing mental health system. In order for accurate assessment to be made, reliable data on prevalence and the functionality of the mental health system must be analysed. In many developing countries, this is the first problem encountered, as there is a distinct lack of valid data available on the effectiveness of existing interventions. South Africa is no exception in this regard. South African researchers involved in the project suggested a key element in improving mental health care systems would be the development of systematic strategies to monitor and evaluate existing systems. Robertson and company, the South African researchers, were however able to supply statistics regarding budget distribution in March 1998. At that time, 8.5% of the South African Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was spent on the health sector – only 2.5% of this amount was channelled to mental health. Furthermore, 95% of the mental health budget was spent on institutional care. The researchers thus concluded that the public health service in South Africa is stunted because of its unhealthy competition with other departments for government funding. The statistics also suggest that government support for community work in mental health is neglected.

In further examining the flaws in the current South African health system, Robertson et co. identified the lack of resources, planning and implementation of mental health care systems as well as the overcrowded and understaffed primary care services (maintained by undertrained staff) as negative variables in need of urgent attention. Poverty presents a significant threat despite the fact that South Africa is one of the more affluent nations in sub-saharan Africa. Theft and gang-related violence is another country-specific problem that needs to be addressed.

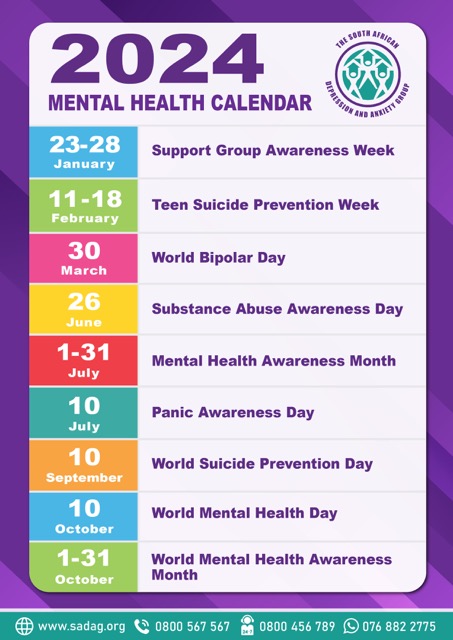

The researchers identified that there are only 15 NGOs active in the mental health sector in South Africa. NGOs can play a vital role in mental health by bridging the gap between patients and professionals. In many cases, advocacy and support groups take on the responsibility of not only supporting and educating patients, but of educating a very cynical public. One such group in South Africa, the Depression and Anxiety Support Group, is the first support group to take the initiative of infiltrating disadvantaged and rural communities through education and support programmes. The group is the largest private mental health care initiative in South Africa, with over 80 regional support groups active throughout the country – 28 have been specifically created for previously disadvantaged communities. The group interfaces with a broad network of professionals and its members have easy access to an extensive referral system to supportive health professionals. In recognition of the group’s groundbreaking work, the SA Federation of Mental Health and the World Health Organisation recently honoured the group with an award for “reaching service users in previously disadvantaged groups” and “creating several support groups in hitherto unserved areas”. There is a great need for further interventions and other such groups in South Africa.

The Depression and Anxiety Support Group has also been pro-active in establishing productive partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry. Several pharmaceutical companies collaborate closely with the group, supplying patients with as much information as possible and assisting them in making use of available medication. This kind of partnership challenges the traditional model of sponsorship in which the private sector merely contribute donations to charities without imparting valuable knowledge, skills and resources.

Once all the existing interventions have been analysed, researchers can then progress to the second stage of planning more appropriate interventions to be implemented in order to improve the state of mental health in a particular country. This would involve highlighting those groups that are at the greatest risk – normally the more disadvantaged and deprived groups – and exploring the mechanisms and resources available for implementing changes. Often there are a complexity of problems that must be dealt with. Good interventions are normally culturally-appropriate, easily replicated and easily sustained. It is advantageous for interventions to meet a broad need at low cost, with a low use of specialised staff.

Once interventions have been implemented, they should be re-assessed consistently. Staff should be correctly trained in policy implementation strategies. A strong need also exists for the development of innovative, complementary methods, which can detect and effectively manage common mental disorders.

Improving mental health in developing countries remains a difficult task. By applying the correct principles and remaining pro-active, much can be achieved. The accomplishments of advocacy groups, such as the South African Depression and Anxiety Support Group, and sponsored projects, such as “Epilweni”, which supplies the Khayelitsha community with psychiatric, medical, social and educational services, are proof that well-thought out interventions can have a significant impact on the overall mental health of developing countries.